Armstrong’s Places

Cragside: the palace of a modern magician

‘I can’t begin to convey the faintest idea of the pleasure that Cragside has given me,’ said William Armstrong a few years before he died. ‘I feel certain that, had there been no Cragside, I shouldn’t have been speaking to you today – for it has been my very life.’

Described from the early days as ‘the palace of a modern magician’, Cragside House was created by William and Margaret Armstrong in the late 19th century amid the treeless moorland of Northumberland, near Rothbury and the River Coquet. The availability of a powerful water supply that could be harnessed to drive machinery was crucial to the choice of location.

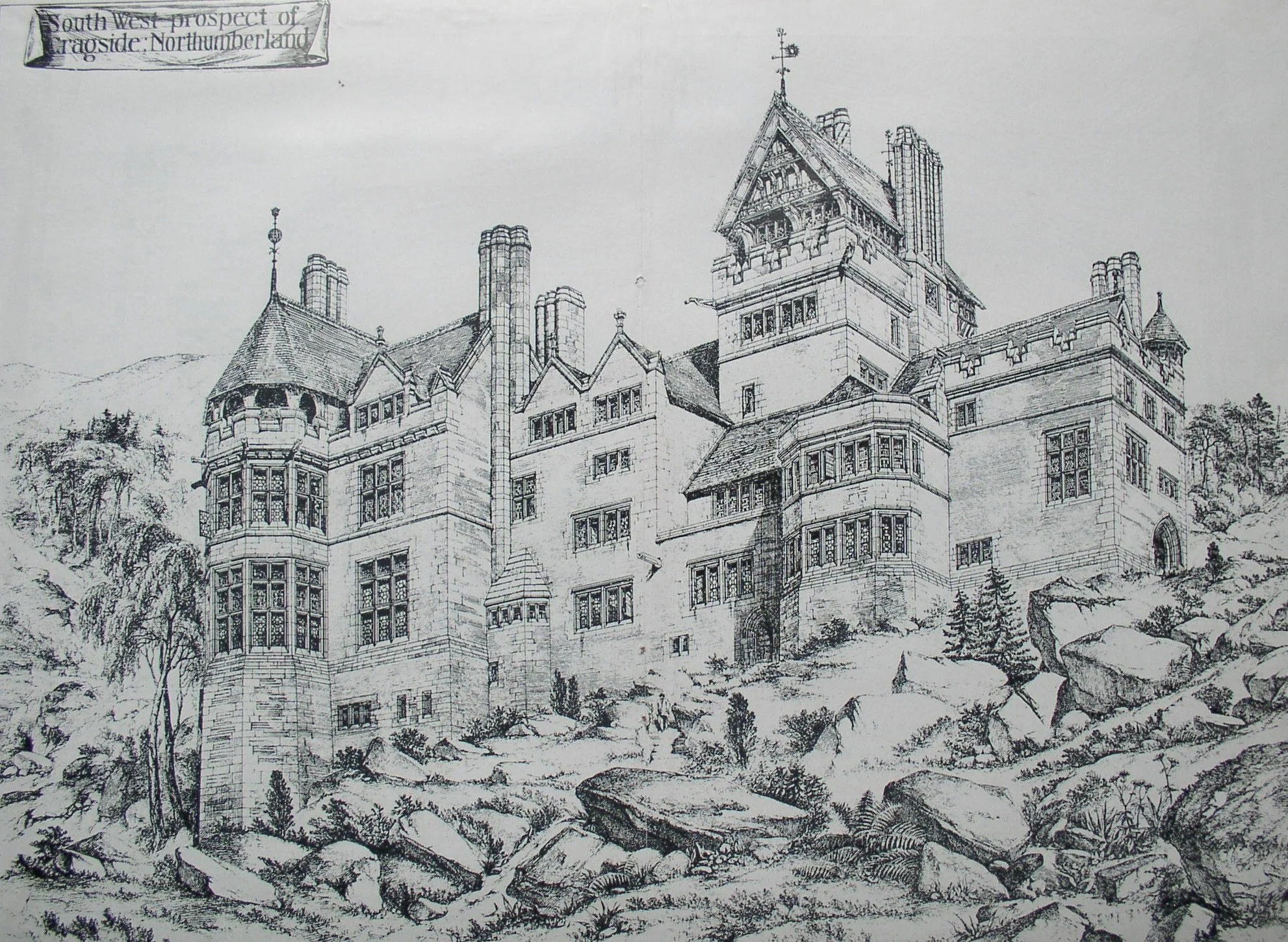

Cragside began life in the mid-1860s as a humble sporting lodge, but everything changed with the arrival on the scene of the visionary architect Richard Norman Shaw. Shaw was involved in the development of Cragside over a period of 15 years, during which the house grew and grew.

Even when Shaw had finished his work – and the Armstrongs had planted millions of trees on the estate – the house remained dramatically exposed in its setting. In the opinion of architectural historian Mark Girouard, it must have looked more like a castle than a house: ‘It was floating on the top of a craggy hillside, as you can see in the old photographs. Now the trees have grown up all round it, which give it a curious, rather spooky character. It’s a kind of magic place.’

This sense of magic was enhanced by the extraordinary inventions that Armstrong put to work at the property, many of them dependent on water power. Most notably, in December 1880 Cragside became the first house in the world to be lit by hydroelectricity. It was this and other ‘mod cons’ that prompted a three-day visit in 1884 by the royal family, the future King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra and their five children.

A century later, Cragside was handed over to the National Trust National Trust, and has since become one of the Trust’s most visited properties in the north of England.

Its importance is captured in The English House by Dan Cruickshank, reviewed by Rowan Moore in the Observer.

An early vision of Cragside by Richard Norman Shaw RA. The house as built did not exactly match this drawing. (Laing Gallery, Newcastle)

The poet John Betjeman, who said that he would like to have lived at Cragside, had a theory to explain its genesis. ‘First, I think, Armstrong was going to create a castle. And then he decided, or somebody decided, to add [a dining hall, a library, a gallery], so the castle as you came in was immense, its stone arches . . . and passages never quite ending, leading you on to another corner. And then they decided to go for pleasure and not be such a fortress, so there is the ballroom part in the Renaissance style – most beautifully done, and a fireplace as big as a house in the ballroom with alabaster carving all over it. I’ve never seen anything like it, never seen anything so big before.’

Armstrong entertains three princes during the 1884 royal visit to Cragside. Two of them would become king, as Edward VII and George V. (Painting by H. H. Emmerson, Cragside)

Newcastle upon Tyne

There are reminders of William Armstrong everywhere in Newcastle, the city of his birth and the heart of his industrial empire, but the only formal memorial to him is the statue by William Hamo Thornycroft standing outside the Hancock Museum (now the Great North Museum: Hancock).

This is an omission that The Armstrong Project seeks to address by the restoration and regeneration of Jesmond Dene and the Banqueting Hall, which he gave to the citizens of Newcastle. The Armstrong Bridge, which links the two sides of the Dene, was built by him.

For 40 years, from 1860 until his death in 1900, Armstrong was president of the Literary and Philosophical Society of Newcastle upon Tyne (the Lit & Phil), the centre of intellectual life in the city for much of the 19th century and still going strong today. He helped to found the College of Science, which evolved into Newcastle University. The centrepiece of the modern university is the Armstrong Building, of which he laid the foundation stone in 1887. He and his wife set up the Elswick Mechanics’ Institute and schools for workers’ children, and they endowed seven hospitals.

The Swing Bridge across the Tyne is a powerful reminder of Armstrong’s mastery of the science of hydraulics – reflected later, even more impressively, in the workings of Tower Bridge in London. Elswick, a mile further up the Tyne, was the site of his hydraulics works, opened in 1845. This small factory grew and grew until it occupied a frontage of 1½ miles along the river, producing hydraulic machinery, gun and ships for all the world’s navies. At the start of the 20th century, Elswick Works employed 25,000 people – a figure that rose dramatically in times of war – but few vestiges of it survive today.

The River Tyne’s swing bridge replaced a multi-arched stone bridge that had prevented ships from travelling upriver to Elswick.

Bamburgh Castle: cornerstone of England

Described by the historian Cadwallader Bates as ‘the very cornerstone of England’, Bamburgh Castle was bought by Armstrong in 1894 – in a ruinous state after hundreds of years of neglect. Aided by architect Charles Ferguson, Armstrong embarked on a massive programme of renovations, intending to turn part of the castle into a convalescent home for people who had seen better days – but he did not live to see result, dying in 1900 at the age of 90. The restoration works, which took ten years to complete, were reckoned to have cost more than £1 million.

The castle is still owned by members of the Armstrong family and much of it is let as private apartments, although other areas are open to the public and can be visited throughout the year, including the Great Kitchen, the King’s Hall, the Captain’s Lodging and part of the keep, including the Armoury.

Bamburgh is a magnet for film-makers. Celebrated directors who have been drawn to the spot include Roman Polanski (Macbeth, 1971), Ken Russell (The Devils, 1971) and Shekhar Kapur (Elizabeth, 1998). Becket starring Richard Burton and Peter O’Toole was made at the castle in 1964, and Mary Queen of Scots with Glenda Jackson in 1972. More recently, it featured as a backdrop in Danny Boyle’s post-apocalyptic horror film 28 Years Later (2025), which was set partly on Holy Island.

Restoration of the King’s Hall gets under way in late 1890s under the direction of architect Charles Ferguson.

Bamburgh Castle as it appears today, from the seaward side.